Adam Roberts is a noted writer and scholar of science fiction—he’s written academic texts such as The History of Science Fiction (an indispensable book if you’re interested at all in the history of the genre) and books like New Model Army, Jack Glass, and Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea.

His latest release is something different altogether: a novella from fiction start-up NeoText—the same publisher that recently released Maurice Broaddus’s illustrated novella Sorcerers.

Here’s the description of the book from NeoText:

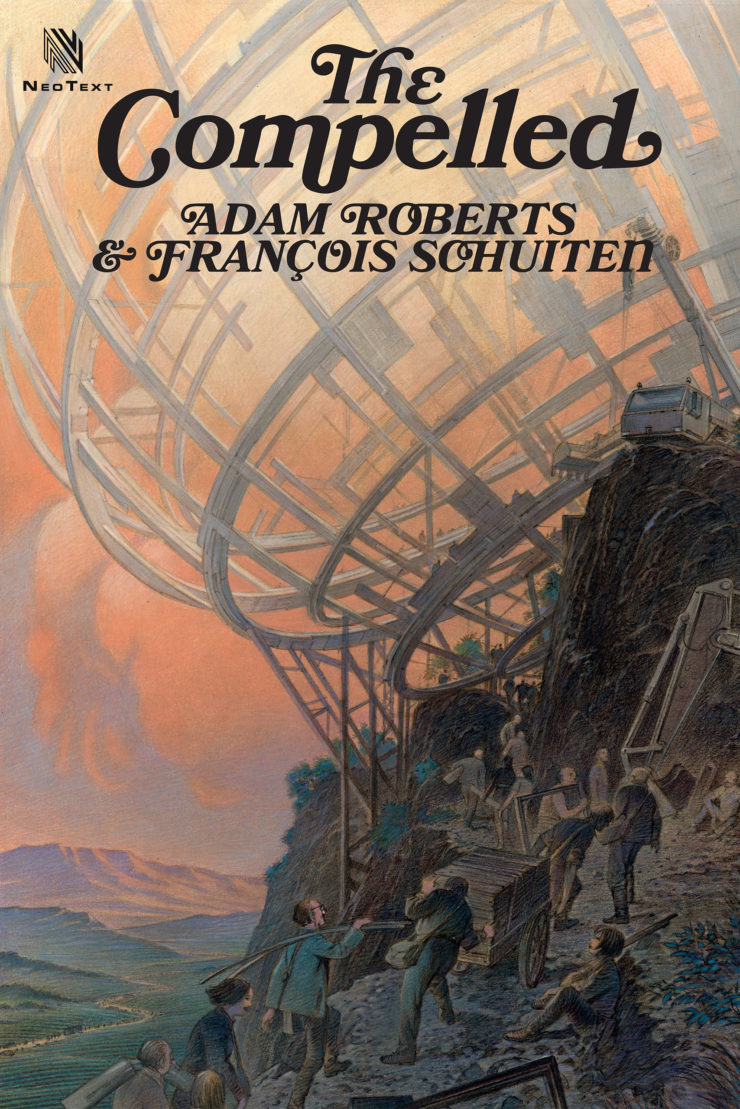

A mysterious change has occurred in humanity. Nobody knows how, why or exactly when this change came about, but disparate, seemingly unconnected people have become afflicted with the uncontrollable desire to take objects and move them to other places, where the objects gather and begin to form increasingly alien, monolithic structures that appear to have vast technological implications. Some of the objects are innocuous everyday things—like a butter knife taken still greasy from a breakfast table or a dented cap popped off a bottle of beer. Others are far more complex—like the turbine of an experimental jet engine or the core of a mysterious weapon left over from the darkest days of WWII.

Where is the Compulsion coming from? And— more importantly—when the machines they’re building finally turn on, what are they going to do?

I spoke with Roberts about the novella and what inspired it.

In The Compelled, you present a world in which people are strangely compelled to move seemingly-random objects to seemingly random places, and it becomes clear that there’s something larger at play. Can you walk me through what inspired this story?

Adam Roberts: The initial concept was John Schoenfelder’s. He came to me, in the early stages of laying the groundwork for NeoText, with two propositions: one that I take this premise (that people are driven for reasons they don’t understand to take various kinds of stuff and place it elsewhere, such that strange structures and even alien machines begin to be assembled, and nobody knows why) and run with it, write a short novel exploring it and developing it.

The other was the opportunity of working with François Schuiten. Both were pretty exciting to me, I must say. John then gave me and François carte blanche to develop the concept any way we wanted.

This story comes at a time when we’re experiencing some social upheaval through major movements, leading to clashes with police and authorities around the world: has that experience figured into the world that you present here?

AR: The first draft of the story was finished before the present widespread social disaffection really became the thing it is now. I mean, the social disruptions of the premise meant that I had to write some of that but the story was pretty set. The concept of the story is that the “compulsion” effects people randomly, irrespective of race and class and so on; so riot-police lockdown isn’t focussed on one group or set of groups, it’s general.

It might be interesting to think how I might have written the story if it had been, say, *just* people of color who are affected by it … an intriguing notion, but different to the story I’ve actually written!

How did this collaboration with NeoText come about, and what was the process like to work with a new reading startup? What does this particular publisher offer the reader that others don’t?

AR: I had several conversations with John, and the other people at NeoText, about what they are hoping to achieve on a couple of fronts. One is that traditional publishing knows how to do regular text-based books (in hard-copy and audio-book form, less so with ebooks maybe) and graphic novels (though they’re often quite pricey) but that the ebook form allows a canny publisher to put our reasonably-priced and lavishly illustrated shorter novels that will, hopefully, appeal to lots of people.

Hard to do that in hard-copy without costs going through the roof. I think that’s right, and that the kind of books NeoText are putting out fill a gap in the market: original fiction with lots of high-quality illustrations. The other is film, something John (a film producer as well as a publisher) knows about. So far as that goes, he thinks the time is ripe to diversify movie productions a little, to move things away from Extruded Hollywood Product, reboots and endless sequels, to find interesting, original, even unusual stories to make films out of. Amen to that, I say.

The illustrations are key here, too. After all, nobody wanted to finance Alien until Scott went away and returned with Giger’s cool artwork to help producers visualize how it might go. Then they were all over it.

How did you collaborate with François Schuiten when it came to creating the artwork? How does the art add to the text, and vice-versa?

AR: François is great; it was a pleasure and an honor to hang out with him. I took the train over to Paris a couple of times to chat with him about how to develop the story in ways that would best suit his illustration style, which (visiting Paris, sitting in his apartment as he sketched possibles in front of me, lunching in a Montparnasse café in the sunshine, chatting about art and science fiction) was very far from being a hardship.

Plus, of course, he’s a giant of the contemporary bande dessinée world. The only wrinkle was that his English isn’t wholly fluent, so his partner stayed with us to help translate. Now, I speak a bit of French, but … the truth is I speak French like an Englishman. Badly, and with an atrocious accent. Nonetheless after a while his partner figured: oh, Adam speaks French, I’m not needed, and went off to do her own thing. It was fine for a while, but as the day went on, and especially after the wine was opened, and Francois began speaking more rapidly and more idiomatically … well there’s only so many times you can say to a person “excuse me, could you repeat that? I didn’t quite catch …” So towards the end I was smiling and nodding and getting a, shall we say, more impressionistic sense of what he was hoping to do with the art. It worked out OK in the end, so maybe that was a bonus, actually. Perhaps more people should try it.

What do you hope the reader takes away from The Compelled?

AR: I hope they enjoy it, obviously! The best science fiction makes you want to turn the page, strikes you as beautiful and thought-provoking and stays with you after you’ve finished. In this case, I have the advantage on being carried along by François’s extraordinary art.

The Compelled is now available from digital retailers.